Security has an effectiveness problem

There's a lot of factors to consider, including engineering velocity

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed are solely my own and do not express the views or opinions of my employer or any other entities with which I am affiliated.

Big news for those who missed it! There’s a permanent price drop for my blog. It’s now $5 monthly and $49 annually. If you want to support me at my old rate, feel free to enter that amount into the founder member’s rate.

If you’ve been looking to subscribe, now might be your time!

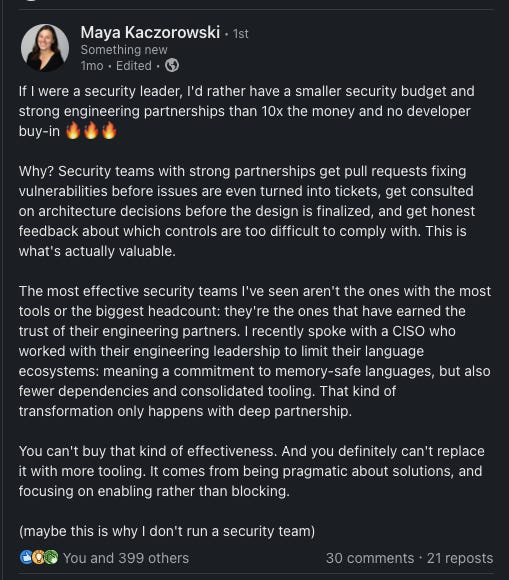

Occasionally, I scroll through LinkedIn posts to find inspiration for future newsletters. This weekend, I went through and found this one by Maya Kaczorowski.

For those who are familiar with my blog, you know I strongly advocate for many of the ideas in her post. However, Maya goes beyond by arguing how aligning security more closely with engineering makes security (and possibly also engineering) more effective. This is especially compelling as executives want to push for more efficient operations. There are two major implications. First, many security teams are overstaffed. Second, tools aren’t the only way to make security organizations more efficient — having stronger partnerships is a “free” way to do this.

Of course, developing these partnerships is hard. I’ve written about how both security and engineering can be better partners.

In fact, I’ve gone so far as to say that security teams should have more software engineers. It is much easier to partner when the asking side, i.e. security, has empathy and visibility into the other’s workflows.

I’m realistic here — having a shift is an uphill battle. It’s already difficult to hire software engineers, let alone ones who want to work in security! Regardless, for the reasons that Maya highlights, having a few software engineers as key members of your security team can be useful.

There are a few caveats here of course. Despite my push for a more engineering-forward security organization, I don’t think it’s for every company. This is primarily meant for companies that heavily rely on technology for their business. However, nowadays, most companies fall into that category. Unfortunately, security has been slow to adapt to this reality. That is, for most companies, the major risks require some engineering knowledge to fully understand and mitigate.

The key is to understand what role security plays in your organization. Is its job to find and surface risks, or is it also responsible for fixing and mitigating them? The former doesn’t require any software engineers, but more subtle and nuanced risks, such as business logic issues in the application, require more technical expertise.

The question comes down to how you measure effectiveness. The problem is that most company leaders and executives don’t quite understand what they truly want. They might want someone to fix the risks, but they hire a security leader who builds an organization that’s primarily surfacing them and asking engineering to fix them. Although you ultimately get the desired result, one approach comes at a higher cost.

Jonathan Price, director of security operations at Grafana, wrote an article saying how security has a pricing problem. Of course, it’s a fact that many of us know, but his reasoning behind it points to some systemic issues:

Many security practitioners are not software engineers by training, have little idea of how a product is built or the costs involved, and have limited ability to build it themselves.

There’s less OSS footprint in the security space, and most of what exists is only usable by a few technical teams.

Security products tend to have higher barriers to entry. Many products require significant up-front data investment to identify enough issues to be valuable. It’s harder for security teams to build tooling on top of a smaller, core product, so security products need to be more feature-complete to compete. If you’re familiar with crossing the chasm, security sales tend to start somewhere in the early majority; there aren’t many innovators and early adopters to sell to.

He says that security’s inability to understand how products are built and thus their value is causing substantial issues:

This pricing dynamic is holding our industry back.

It hurts organizations and companies having to pay the prices. It’s hard to fund a security program or spin one up quickly with more than a handful of tools. This limits the effectiveness of teams; every cost tradeoff they make makes their org less secure. This especially hurts smaller companies and startups. If you're a 30-person series A company, even if you care deeply about security, it's hard to find the money for a single dedicated security hire. Let alone the 7 figure tools budget they may want to bring in.

What’s interesting here is that through this Substack article, he points the blame at a systemic issue with the way security organizations are run that’s actually perpetuating this price dynamic. It’s even more concerning that he believes security people don’t know how a product is built. If they don’t know how products in their domain are built, how are they able to secure their own company’s products?

This all comes back to what an effective security organization means to a company. Which of the following do you want?

A security team with software engineers assists a product engineering team early in the design process and prevents vulnerabilities from being introduced. With the help of the security team, it’s likely the product will ship on time with fewer issues.

A product engineering team doesn’t trust the security team will understand the product feature, so they build until the security review during which the security team discovers some issues and delays the launch, leaving the software engineers to fix the issues.

Both might achieve the same result, but the first one is preferable and definitely seems more effective than the second. However, it’s rarely caught in the security metrics that everyone uses. Most security metrics are operational because it’s easier to measure, e.g. number of vulnerabilities fixed, time to response, etc. Maya writes another LinkedIn post explaining why this is short-sighted.

The point is that these metrics don’t capture many nuances in the process — they can’t measure whether security is helping solve the problems or just merely pointing them out.

Maya suggests “time-to-close” as a metric, but I disagree. It could result in security bothering software engineering more to fix the issue. A better metric might be to measure engineering velocity with and without a security engineer assigned to the team. Similarly, it might be useful to measure the time to ship versus the number of PRs a security engineer does. Another idea is to count the number of features blocked by security.

Honestly, I’m not sure these are the best metrics, and finding the right ones is hard. It might be worth looking at some DevOps metrics to see how they can apply. But sometimes, it just comes down to how often engineering complains about security and how engineering views security: enabler or blocker?

Given the questions about effectiveness and pricing above, does security really need such big budgets? Can we do more with less like other teams have? It seems the answer is yes, especially at scale.

At scale, it’s easy to solve the pricing problem. A company can allocate some software engineers to build and maintain a security tool rather than purchasing an external vendor. The calculation to decide if this path is cheaper is not difficult — I would imagine at scale, it is cheaper to build your own.

Similarly, if a security team is primarily pointing out problems, we can replace some of them with certain tools and/or ask software engineers to do some security work instead. We can replace some of the velocity lost with more software engineers. This will likely be cheaper than hiring more security people.

The issue might be that companies are improperly measuring risk and the cost of reducing it. More security budget doesn’t necessarily lead to risk reduction. It might be coming at the cost of slower engineering velocity, and thus higher business risk. But, thankfully, companies are starting to realize this by limiting and reducing security budgets. In some extreme cases, companies are eliminating large portions of their security organizations.

Many signs point to an effectiveness problem in security — why are there so many tools, but it seems like security isn’t getting better? I don’t have a good or simple solution. Maybe, more people like Maya should be security leaders!